Unit Three Critical Reflection

Critical Reflection: Still Life

In Western art, still life painting has long depicted immobile man-made and natural objects. On the other hand, it is imperative to acknowledge that it has also found application in describing modern advancements in photography, capturing the essence of still life in motion. The boundary between these two distinct disciplines, painting and photography, has become porous—especially amidst the surrounding ecology of media images and their continuously evolving landscape. This project investigates the disjointed simultaneity of today's media landscape in a way that creatively expands on the historical concept of still life. The title “Still Life” teases with hints of anachronism and traditional painting categorisation. Meanwhile, the artworks establish their contemporary relevance by capturing the blurred simultaneity fostered by our modern media network, employing the photographic attributes of what we can term contemporary still life, capturing a still moment in photographic reproduction. Among the artistic genres shaping and rendering time experiential, still life occupies a unique position. Still life challenges contemporary notions of time in two significant ways: firstly, it seizes a moment devoid of temporal progression, and secondly, it prompts viewers to discover hidden potentialities within the present moment. In contrast to perceiving pictures as static representations devoid of real meaning and agency, “Still Life” adopts a critical, analytical, and interpretive standpoint emphasising pictures' inherent movement and volatility. Images travel through bodily experiences and circulate within networks at varying speeds. Ultimately, they perpetually replicate and transpire, irrespective of the distinctiveness of their subjects. Establishing a framework for comprehending our relationship with images enables a shift from passive modes of observation to a state where the picture becomes a channel for thought. We no longer perceive ourselves as merely standing in front of a framed image; instead, we pass through and beyond it, where one exists within and through the other. This perspective shifts the focus from presenting a singular object to embracing an exhibition approach that prioritises active involvement, intellectual exploration, and the immediate impact of still life.

In the book What Do Pictures Want?, W.J.T. Mitchell examines diverse topics such as metapictures, cloned sheep, and fetishism, presenting his significant ideas by attributing human-like desires to images. Mitchell's theoretical perspective on visual culture delves deeply into the analysis of social practices intertwined with human visuality. This approach sensitively highlights the impact of images on our bodily experiences, prompting contemplation on how their influence evolves in tandem with cultural and social changes. Mitchell's critique offers a comprehensive framework of visual culture that goes beyond matters of taste and makes broad philosophical statements about current socioeconomic conditions. What he makes clear is that pictures are continuously evolving and transpiring; there are no still images, and as such, no such picture can ever be singular. As he states, ‘Pictures, including world pictures, have always been with us, and there is no getting beyond pictures, to a more authentic relationship with Being, with the Real, or with the World.’ (Mitchel, 2005, p. xiv) This insight prompts contemplation of paintings' temporal dimension. Time is an element of experience that can be analysed and interpreted in numerous ways. Cultural conditions of perception and interpretation always determine how time is gauged, represented, experienced, and assessed, as the temporal serves as the sole medium through which time can be recognised, given its imperceptible nature. Therefore, the only way to experience it is through immanent means, such as objects or movements. It follows that the passage of time is inextricably linked to the aesthetic processes of representation, to the interaction of media networks and visual culture. The coexistence of the present and the past in a painting raises the question of where painting fits in the connected world of today and the distinctive visual languages that develop with contemporary technology. It is not entirely evident what makes a picture unquestionably a work dominating the features of a specific epoch in visual histories or what characterises a painting from this era. Time is made more convoluted by the contemporary state of global visual culture, which is at once divided by geopolitical veracities and linked by a common internet image network. Moreover, one could contend that the significance of attributes such as an artwork's place of origin or its method of production in shaping its conventional classification is diminishing. So, in the age of the networked image, is it possible to interrupt the continuous ebb and flow of pictures and the apparent accessibility of a wide variety of visual representations?

The presented paintings' meticulous attention to detail and craftsmanship immediately captivates the viewer, compelling them to engage in prolonged observation: a slowing down, a stilling. Simultaneously, the imagery instils a sense of unease or perplexity. The artworks convincingly portray a meticulously mirrored reality that implies something more profound than what they directly show. The collection of images is sourced from photojournalist magazines, removed from their original political or narrative context. The unassuming nature of the subjects discourages symbolic interpretation, intentionally maintaining a neutral or commonplace quality. Underneath the surface of these conventional motifs, the paintings vigorously explore fundamental inquiries regarding the essence of painting and the nature of the picture. This exploration renews the ongoing query about how the subject relates to its portrayal. This subject has persistently concerned art discourse throughout history, most notably in the last decade with the influence of modernism through art critic Clement Greenberg. Greenberg, known for his instrumental role in developing medium-specific theory, is often criticised for allegedly pushing art towards banality through his narrow and simplistic approach to the medium. His advocacy for abstract and formalist abstraction favoured the investigation of formal elements like colour, line, and composition over representational content. By promoting non-representational art, he lessened the reliance on painting as a tool for depicting external realities or narratives, encouraging artists to concentrate on the inherent qualities of the medium itself. In this context, the term medium-specificity remains relevant, providing an aesthetic framework that reinforces the very essence of art. This framework does not advocate for a strictly formalist classification of specificity. Instead, it raises concerns not only about the portrayal of representation in painting but also about the secular characteristics of art on a broader scale and its role in visual culture and historical discourse. By tracing the impact of visual representations and the artistic methods that seek to confront them within the material and structural aspects of the painting, questions arise regarding the extent to which contemporary techniques oppose, or instead align with, the prevailing systems of control and their influence on subjectivity.

The age-old philosophical and theological question of what constitutes the true nature of reality vs what is merely apparent is at the heart of this enquiry. It raises the question of whether a picture (or painting) can ever be more than a facsimile of reality. While paying homage to modernist achievements, these paintings venture into the realm of visual illusion, encapsulating the very essence of a three-dimensional reality within the constraints of a two-dimensional canvas. Lessons from experience emphasise that a painting's essence transcends its subject and motif, although these undoubtedly influence the artwork's aesthetic appeal and intellectual resonance. In the contemporary art scene, adherence to conventional subject matter remains prevalent, yet we have yet to sever our ties with modernism's pursuit of art as an autonomous and self-contained entity. This lingering bond elicits concerns that the artwork might indeed reflect the world in its entirety, echoing a profound connection between the real and the represented. The inseparable connection between painting and image, interwoven in a dialectical relationship, continues to generate significant unease. The discomfort emerges from the idea that painting predominantly functions as a tool or method for manipulating materials that frequently appear to challenge the subjects they depict, consequently influencing the overall composition of the artwork. A paradoxical outcome of engaging with a painting is that the viewer consistently perceives two elements simultaneously: the depicted figure or form and the flat surface of the medium. This contradictory experience is born within the viewer's gaze, where two distinct worlds converge to shape one's interpretation. This dynamic gives rise to an undeniably captivating discord.

Gerhard Richter, Betty, 1988, 102 cm x 72 cm, Oil on canvas

Considering how easily their technical skill and virtuosity may overshadow or undercut this essential attribute, this group of paintings, with their blatantly duplicated reality, seem to yield even more to this dissonance. There is a mutually tensional and enriching relationship between the medium's materiality and the representation's fictionality. The fascinating connection occurs as the viewer becomes cognizant of the physicality of oil on canvas while simultaneously experiencing the illusion of replication as the two tenets coexist. It is when one only realises that these paintings are not representations of reality but rather "photo-paintings" that the true nature of the artwork becomes apparent. The paintings derive a multitude of images from various photojournalistic magazines and digital reproductions, each carrying its own set of imperfections. They intensify the immediacy of photographic elements within the paintings through the interplay of compositions and collages, accentuating imperfections such as blurring and pixelation. This has been demonstrated by renowned artists such as Gerhard Richter, who stated that he does "not use it as a means to painting but use painting as a means to photography.” (Richter, 1995, pg. 73) The language shifts when the viewer's perception is altered by the tactile presence of the work, semantically pointing to the material attributes of pictures as objects. Consequently, the subject depicted no longer maintains a stable position in relation to the picture plane. The artwork compels us to readjust our perception instead of encountering a consistent image akin to the customary techniques employed in oil painting. It is conceivable that within the confines of the stringent and artificial norms of digital media, the authentic reality momentarily emerges through the tangible qualities of the representation. Paradoxically, the representations of the virtual and artificial world from the past might serve as a conduit to bring us closer to empirical reality. In other words, the viewer's perception of the artwork oscillates between the virtual portrayal and the tangible qualities of its source as a reproduction.

A Pipe Dream, oil on canvas, painted frame, Blue PVC Fuel Hose Pipe, 24 x 32.5 x 5.5 cm (framed), 39.5 x 41 x 5.5 cm (overall)

One example created to investigate and create this oscillation between the real and the imagined is the work A Pipe Dream, in which the subject matter encompasses a pipe. Yet, an actual pipe has been incorporated into its framing, whilst the image has been cropped and isolated within a picture plane, eliminating all reference to its original setting. Since neither the source nor the intended application of the painting is directly evident, the artwork appears bereft of a contextual reference. The work is keenly attuned to the reality that transformations of a picture might appear in a variety of contexts and media. In essence, it tracks the unprecedented shift in the global economy of pictures, which inevitably profoundly affects painting and the field of contemporary art. Consequently, the work circumvents the tendency to revert to obsolete paradigms that support the notion of an immutable and autonomous artistic expression. Likewise, it avoids dependence on the notion of subversion, which in today's world merely perpetuates the mechanisms of the cultural sector that rely on novel aesthetic methods of compression.

The painting process introduces an alternative layer of meaning or genuine substance, as even the ostensibly mundane and inconsequential subject matter receives meticulous attention down to the minutest attention to detail. This perplexing outward appearance is executed with the requisite painterly intensity to concretise the illusion of pictorial representation within the physicality of the painting. Consequently, the depicted subject matter becomes manifest solely within the representation, within the pictorial reality of the artwork; it is indeed the essence of its representation. Thus, the objective motif assumes heightened significance in the creative process, potentially aligning with both the artistic application of paint and the viewer's intellectual enquiry. The materiality of the painting extends into the intangible realm of perception, where the motif triggers recollections and associations, yearning to be compared to the reality depicted in the artwork. However, the inherent intrigue does not solely reside in the reality itself; rather, its subtle planarity and omnipresence project a sense of concentration and contemplation, imbuing the artworks with complexity. These paintings encapsulate an immediate present, an eternal moment in the realm of art, wherein the inexhaustible passage of time elucidates both the visible and the concealed.

The extensive assemblage of works in this collection also represented a somewhat self-contained component in which the individual images, owing to their reproduction, could initially appear perplexing. Upon closer examination, it becomes evident that each picture was meticulously rendered as a distinct entity, bestowing the same exacting precision on every painting, regardless of the subject matter. This uniform attention to detail persists throughout the body of work despite the hierarchal subject matter, wherein the collection subverts the primacy of the individual object. Instead, it places emphasis on composition and painterly effects, elevating them as the primary focal points within the paintings. By guiding the viewer's attention towards these palpable elements, it accentuates the source image that served as the basis for the painting, thus emphasising the contrived quality inherent in pictorial replication. There is complete care given in the craftmanship of painting, to the colour and value to assimilate an absolute realism to the reproduction that shows an affinity with the paintings in its virtuoso conquest of the problem of mimesis and its creation of an absolute reality. The incorporation of mass media imagery in this collection of photo paintings serves as a conspicuous demonstration of the critical involvement in the influence of mass media on the formation of contemporary visual culture. This engagement encourages viewers to re-evaluate the repercussions of media imagery on collective perception and the construction of historical memory.

Going to See a Man About a Dog, oil on canvas, painted frame, 21 x 29.7 cm (A4, unframed) 24 x 32.5 x 5.5 cm (framed)

Isolated imagery appears omnipresent, uncanny, or bleak until the title provides enhanced meaning and context. By isolating and modifying images, artists draw our focus to their underlying meanings and decide not on the basis of our immediate encounter with the subject but on the basis of our connections with other images that are conceptually similar to the one in question. Douglas Crimp posits that the Pictures Generation artists resort to the prevailing images within their cultural milieu; however, they disrupt the conventional signifying role of these images, disassociating them from their usual captions, commentaries, and narrative sequences. In doing so, they challenge the illusion that these images are inherently transparent conduits to a signified. Crimp quotes Walter Benjamin's The Short History of Photography (1931) in his article titled Pictures, writing, "The caption will become the most significant component of the photograph." (Crimp, 1977, pg. 5). In a similar vein, the works challenge the conventional interpretation of image consumption by negating the cultural and linguistic weight of titles, texts, and language in an effort to pervert our normal visual perceptions. For instance, the painting entitled Going to See a Man About a Dog has a double entendre: the depiction portrays a man and a dog, but the title is also used as an idiom, predominantly of British origin, generally used to conceal one's true destination. The paintings' titles barely go beyond denotations of what they purportedly portray, and yet their playfulness and use of English idioms are both alluring and empty; they seem to capitalise on the individuality of each object while also tending towards the universal.

What becomes particularly intriguing here is how this meticulous craftsmanship and unwavering attention to detail simultaneously assert the uniqueness of each object while subtly gravitating toward the universal. The objects and frames depicted in the paintings give the illusion of singularity despite carrying a spectral aura of displacement and replication. The framing, serving as a symbolic barrier, contains this ceaseless reiteration of mundane motifs within an equally distinctive form. Consequently, the perpetual recurrence of a generic image is imprisoned within a solitary picture plane rather than dispersed across an endless circulation of images. By superimposing a displaced collage of the image down the middle of the image, the man and the dog in Going to See a Man About a Dog are almost completely eradicated so that only their silhouettes, now contained by the stripe that correlates with the proportions of the work's outer frame, remain visible to the viewer. Stripping away the complete form of the man and dog and intentionally severing any authentic connection between the viewer and the observed subjects, the artwork delicately alludes to the elusive essence of a corporeal presence. Not only does the disruption of the work add to the tangible quality of images, but the fluidity of images is arrested rather than disintegrated into disjointed units of data and visual stimuli just prior to their integration into the networks that govern them.

Daniel Sinsel, Untitled, 2023, oil on linen, glass, wire, 118 x 98 x 4 cm

Particularly, the paintings exhibit frames painted to match the dominant colour of the respective image. Thus, it achieves a surprising encapsulation of the authentic image and its presumed aesthetic tropes, resisting the compression typically imposed on imagery in our era of the networked image. This artistic approach involves the transformation of a potentially limitless image into a tangible, three-dimensional form. This form is not easily comprehensible in its entirety, except when displayed on the walls of a designated exhibition space. Consequently, viewers must devote significant time and attention to appreciate the intricate nuances of the artwork fully. This is ushered in the works of Daniel Sinsel, whose work gained fuller recognition following Sadie Cole’s stand at the Frieze art fair. Sinsel skillfully navigates traditional concepts of flatness and spatial tension, delicately balancing on the brink between illusion and reality. Adorning the canvas are minute fragments of glass objects, tangible components that simultaneously defy and coalesce with the illusion of geometric shapes and silk ribbons. Intertwined with the precisely executed painted surface, the assemblage articulates a metaphysical threshold, blurring the lines between representation and reality. “In parallel with this approach, the works reflect an ongoing exploration of conventional realism and chance encounter. Throughout, a dreamlike mood of time suspended, or in flux, prevails.” (Sadie Coles HQ, 2022)

Don’t Make a Monkey Out of Me, 2023, oil on canvas, MDF, pine wood frame, enamel paint, blue fluorescent acrylic plastic, and chrome mirror screws, 101 x 131.5 x 6.7 cm (framed)

The thick frames essentially embody the paintings and bring the real-time setting of the gallery into the visual portrayal. The painting Don't Make a Monkey Out of Me holds relevance within this context, not only due to its sculptural qualities that resist compression in the transmission of images through electronic technology but also for the dualistic interplay it fosters between its figurative representation, illusionary depth, the two-dimensionality of the canvas, and the reflective qualities of acrylic plastic. These elements envelop the observer in a captivating mirage, thereby uniting the artwork with the tangible space. Evident is the unmistakably omnipresent and all-encompassing pictorial realm that extends into the palpable space, paradoxically oscillating between flatness and depth until the boundaries between the artwork, its audience, and the surrounding architecture seamlessly dissolve. The chrome mirror screws that secure in place the translucent acrylic plastic that spans the painting and the frame contribute to the polished, factory-like appearance and, by extension, the reproducibility of contemporary culture. This decorative element not only provides supplementary framing for the assembly of distinct objects but also boldly propels the artwork into the realm of an installation, straddling the boundary between painting and sculpture.

In the Pink, 2023, painted frame, pink fluorescent plexiglass, and chrome mirror screws, 244 x 185 cm

This line of inquiry has served not only the exploration of framing devices for the image but also the curation of the gallery space. The viewer's body is central to all these diverse methods, establishing a connection between them beyond medium barriers as tangential performance. In the Pink forges connections between the artwork and the audience by framing the space in parallel frames that embody both the paintings and participants. The large frame, in a hot pink hue, maintains the same proportions as the painting Don't Make a Monkey Out of Me, albeit on a significantly larger scale, matching the dimensions of the gallery wall at 244cm in height. Employing thematic colours akin to those utilised in the framing of the other paintings harmonises with and enhances the interconnected flow of imagery within the curated installation. This intentional approach serves to unify the separate works, fostering a cohesive integration rather than an isolated coexistence, thereby prompting a contemplation not only of the points at which the works converge but also the interstitial spaces in between. This transitive disposition acts as an extension to the tangible space, referring to a domain elsewhere, outside its materiality. This characteristic is exemplified in the work of Sara Barker. The slender frames assimilate the environments they inhabit, extending delicately yet assertively, even in an intangible manner, toward a signified space. Clearly, by enveloping the space they seemingly occupy, these frames demonstrate a profound level of self-reflexivity within the realm of painterly practices.

Sara Barker, Conversions, 2011, steel, aluminium, various paints, 215 x 115 x 65 cm

By forging connections between the positioning of the artworks, the audience, and the architectural setting, the overarching objective prompts a nuanced examination of the dualities inherent in the reception and consumption of visual information. This comprehensive endeavour strives to delve into the intricacies of aesthetic practices and the emergence of implicit subjectivity, as the deliberate utilisation of space necessitates a recalibration of our focus, encouraging a heightened awareness of our surrounding environment. Enabling a holistic engagement invites an active involvement that transcends passivity, urging the viewer to navigate the artworks and absorb new vantage points and perspectives within an immersive perceptual encounter. As the space of the spectator and the space of the painting become more tightly interwoven, the viewer must thus continually reconcile their sense of the painting as a physical object to their impression of it as a work of fiction and illusion. The artwork prompts the viewer to contemplate not only the painting's subject and painted surface but also the intricate interaction between the painting and our own lived experience.

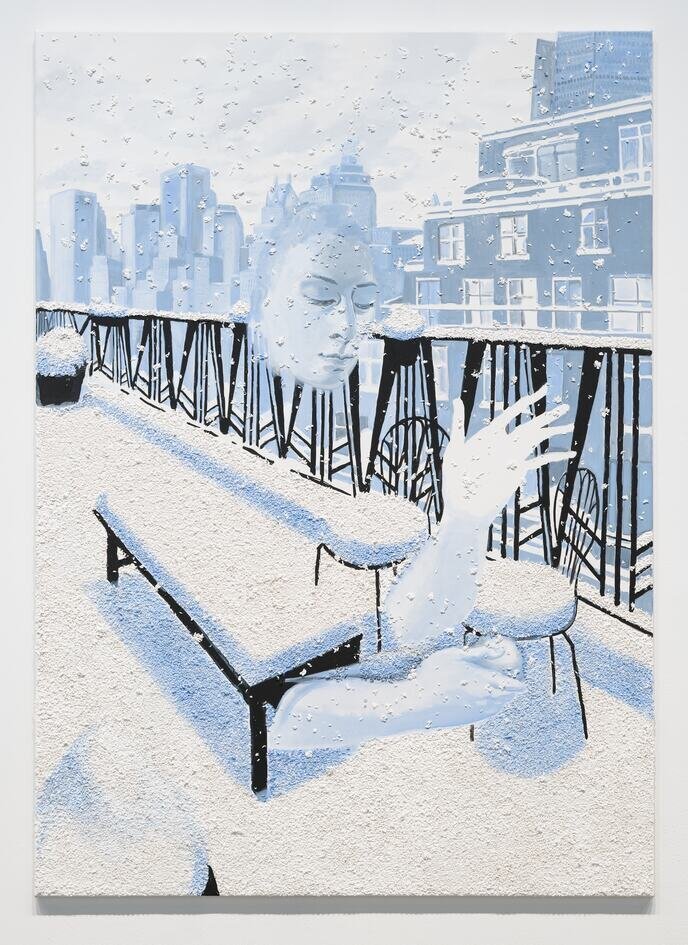

Alison Katz, Slippy, 2017. Acrylic and rice on canvas, 175 x 125 cm. © the artist (2021). Courtesy the artist and The Approach, London.

This relation's innumerable challenges have generously accommodated the lasting influence of visual rather than verbal expression throughout art's developing canon. Vision is the faculty that painting can distinctly lay claim. However, in this case, the exceptional adaptability of the medium and its diverse means of enticing our other senses and sensations in a synesthetic manner are celebrated through a creative engagement of our perceptual capabilities. Allison Katz employs texture to introduce complexity to the painterly vista, challenging the conventional window-like perception of the two-dimensional pane. By incorporating materials like rice into the pigment, as demonstrated in her piece "Slippy," Katz intertwines the physicality of images with our tactile senses, establishing a tangible connection through touch. By embracing Laura Marks's conceptual framework of 'haptic visuality,' which sheds light on how visual representations can be understood and interpreted through a physical encounter, the painting “Slippy” goes beyond traditional visual perception. ‘Haptic visuality’, which involves the engagement of both visual and tactile senses, resonates with the techniques employed in "Paint the Town Red". In this work, integrating diverse textures onto the picture pane elevates the sensory experience, creating a synesthetic engagement that extends beyond the conventional boundaries of visual perception.

Close-up of Paint the Town Red, 2023, oil paint, pumice, acrylic gesso, MDF, pine wood frame, and red enamel paint, 101 x 131.5 x 6.7 cm (framed)

The significance of art lies in its capacity to shape societal perspectives and facilitate the transmission of human experiences across temporal and spatial boundaries. The concept of temporality holds significant relevance in this context as it enables the exploration of how we engage with and assimilate visual information. This exploration leads to a complex network of interconnected temporal and spatial perspectives that extend beyond the realm of self-referential painting. By using a variety of visual methods and historical techniques, the paintings invite the viewer to reflect and play with the comprehension of pictures and their proficiency. A variety of visual techniques—including reflective surfaces, inanimate objects, and collages distort and even disable the compositional relationships that underpin traditional modes of perspectival painting. The paintings feature the kinds of inanimate objects (like pipes and acrylic plastic) that pique aesthetic interest, and as a result, they veer between historical medium and superfluous commercial merchandise before being instantly destabilised, processed, and reformed. Consequently, the appearances of the images depicted in the work are perpetually informed by their past and future conditions and are thus haunted as such by the object's trace. The work essentially elucidates the fundamental premise that lies at the heart of this investigation. It endeavours to merge a vital recognition of the threads that weave through every image with the artistic potential to capture them within the tangible fabric of media networks.

References:

1. Mitchell, W. J. T., 2005. What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2. Obrist, H.U. and Richter, G., 1995. Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of Painting: Writing and Interviews 1962-1993. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd.

3. Committee for the Visual Arts, Incorporated, 1977. Pictures: an exhibition of the work of Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, Philip Smith: Artists Space. [press release] September 24 - October 29, 1977. Available at: https://texts.artistsspace.org/6wdhi1kq [Accessed 22 October 2023].

4. Sadie Coles HQ. 'Daniel Sinsel,' Sadie Coles HQ, Available at: [https://www.sadiecoles.com/exhibitions/890-daniel-sinsel/press_release_text/] (Accessed: 25 October 2023).