Unit Two Critical Reflection and Extended Research

Critical Reflection

I have meticulously painted photographs of various printed materials (culled predominantly from the realms of National Geographic magazines), and I have used a variety of visual techniques—including reflective surfaces, inanimate objects, and collage—to distort and even disable the compositional relationships that underpin traditional modes of perspectival representation in painting. Through my practise in Unit 2, my works have explored the continual circulation of pictures across various conditions and mediums throughout contemporary social networks, devising intricate techniques to make this state of flux tangible within the body of the image. In mutually beneficial ways, the aim of my practise is to disrupt the continuous ebb and flow of pictures and the apparent accessibility of a wide variety of visual representations by drawing attention to their materiality and transparency, by reiterating framing and fabrication-based methodologies. Somewhat tangentially, a hierarchy of photographic genres and applications from the advent of mass consumerism is reflected in this meticulous output. My paintings feature the kinds of inanimate objects (like pipes and acrylic plastic) that pique my aesthetic interest, and as a result, they veer between historical medium and superfluous commercial merchandise before being instantly destabilised, processed, and reformed. Consequently, the appearances of the images depicted in my work are perpetually informed by their past and future conditions and are thus haunted as such by the objects trace.

Installation view: Mantegna’s Dead Christ. Photography by Reinis Lismanis.

While on the subject of spectres, I'd like to mention an exhibition I saw in November called "Mantegna's Dead Christ" by Oliver Osbourne at Union Pacific Gallery after I became aware of his work thanks to the recommendation of Anna Bunting-Branch. Osbourne paints portraits based on historical photographs, imbuing them with enigmatic, malleable motifs that may be revisited and transformed to achieve new perspectives, like ghosts of the past trapped in the vocabulary of their own future revisions. The show as a whole highlighted the history of painting itself through Osborne's use of images from a variety of painting styles and periods. The paintings walk the line between antiquated and neoteric while trying to establish their modernity by depicting the scattered simultaneity that our media network generates. In a painting, the present and the past coexist, and like Oliver Osbourne, I am curious about where painting fits in today's interconnected world and about the unique visual languages that emerge through the use of modern technology. It is not quite clear what constitutes a painting of this period or what makes a picture undeniably a creation dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in visual histories. The concept of time is complicated by the current global visual culture, which is simultaneously split by different geopolitical veracities and united by a shared vocabulary of online images—important to my choice of imagery culled from the realms of photojournalism and much like the brand name, National Geographic. Furthermore, it may be considered that the significance of factors like an artwork's geographical origin or artistic techniques in determining its conventional categorization is dwindling.

Oliver Osbourne, Untitled, 2021, Acrylic on linen, 185 x 145 x 2.7 cm

Figure from the 1804 edition of Della pittura (on painting) by Alberti showing the vanishing point

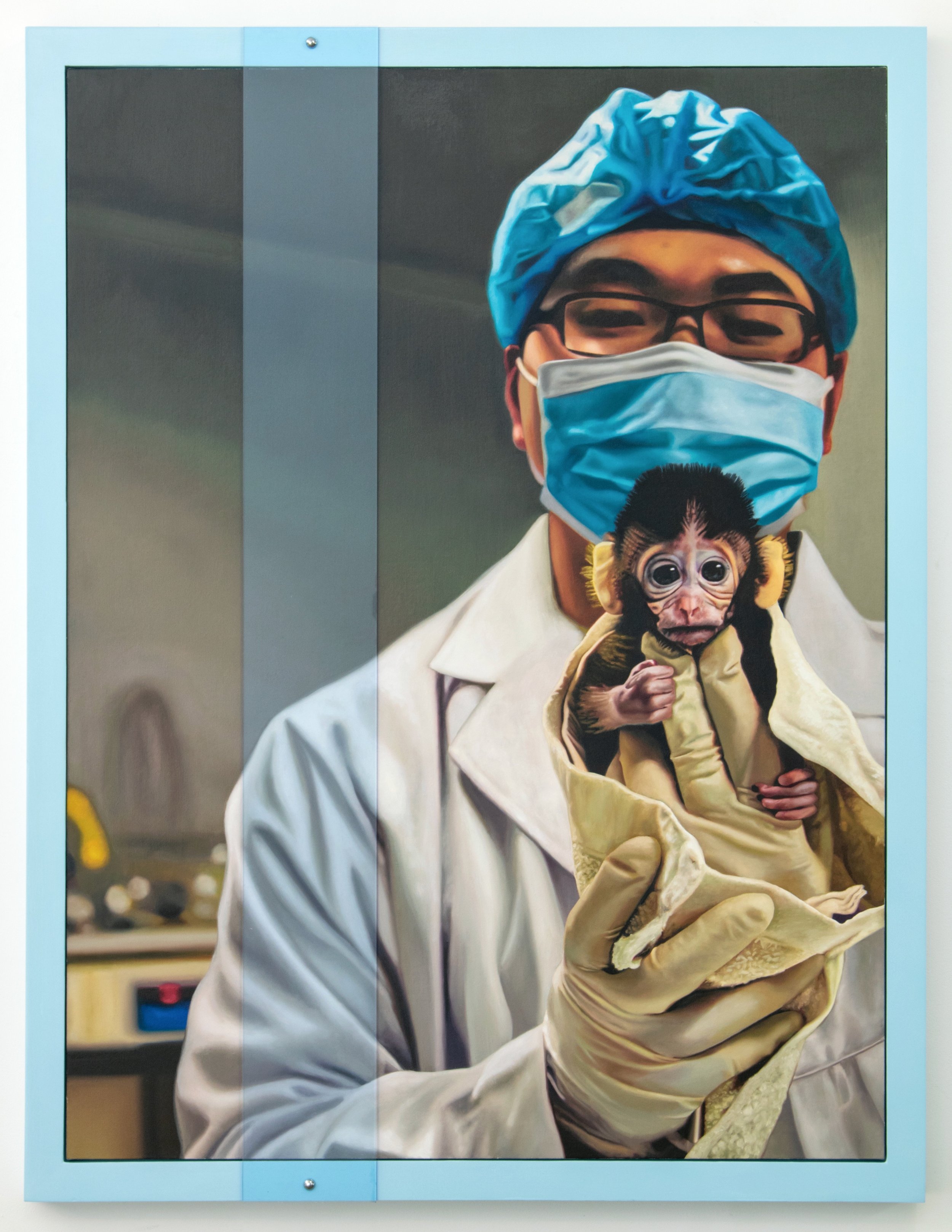

Using a variety of visual methods and historical techniques, the exhibition seemed to reflect on the historical nature of art by transgressively confounding the different nuances of painting, layering the qualities of a particular period into another, and playing with our comprehension of pictures and their proficiency. A large abstract painting of a grid dominated the room, which I found ironic given that the exhibition made reference to a perspectival historical painting and the disproportionate body of Christ in Andrea Mantegna's "The Lamentation over the Dead Christ", which dates back to 1480. Perspectival devices, such as Leon Battista Alberti's book On Painting, which examines vanishing points on a grid, and the compositional rule of thirds, which regulate photographic aesthetics, have been central to my own work, where I have explored the use of perspectival representation in painting and photography. Intriguingly, this observation was made during a Peer Sessions group critique of my Xhbit-exhibited painting "Fifteen Love." Peer Sessions remarked on how the acrylic plastic's ability to multiply horizon lines and form visual triangles enhanced their perception of space. I used the rule of thirds to crop the source photo for my painting "Don't Make a Monkey Out of Me", and I emphasised the effect by including a thin piece of plexiglass in the painting to break up the composition. The chrome mirror screws that secure in place the translucent acrylic plastic that spans the painting and the frame contribute to the polished, factory-like appearance and, by extension, the reproducibility of contemporary culture. Not only does this ornamental feature serve as extra framing for the arrangement of individual objects, but it also clearly shifts the piece to the status of an installation somewhere between a painting and a sculpture. The work essentially elucidates the fundamental premise that lies at the heart of my investigation. It endeavours to merge a vital acknowledgement of the apparitions that pervade every image with the artistic potential of apprehending them within the tangible framework of media images.

Fifteen Love, 2019, oil on canvas, MDF, pine wood frame, enamel paint, green fluorescent acrylic plastic, and chrome mirror screws, 101 x 131.5 x 6.7 cm

Don’t Make a Monkey Out of Me, 2023, oil on canvas, MDF, pine wood frame, enamel paint, blue fluorescent acrylic plastic, and chrome mirror screws, 101 x 131.5 x 6.7 cm (framed)

Oliver Osbourne, Barbara Villiers, 2022, Oil on linen, 50.5 x 45.5 x 6, with frame

Drawing the same lines as Oliver Osbourne, I have encased each painting in thick frames, which essentially embody the paintings and bring the real-time setting of the gallery into the visual portrayal. Osbourne, with a title that alludes almost absurdly to Mantegna's use of perspective trickery in "Mantegna’s Dead Christ", challenges the audience to consider temporal and spatial perspectives as tools for analysing art. To position the works within the discourses of painting, Osborne has made a variety of modest aesthetic decisions, and his invocation of the gallery is just one of them. Oliver has painted Barbara Villiers repeatedly and in varying hues, where they descend into the pervasive green palette that permeates the exhibition, arrested by perspectival tricks of paintings history—perhaps this is why Osbourne referred to the perspectival tricks of Mantegna’s "The Lamentation over the Dead Christ." The ghost of paintings past is then marvellously framed again by its future condition, with a self-portrait of the artist reflected through the mirror of his iPhone in the same tone as the other paintings.

Above are mock up photographs created in Photoshop for my Unit Three Proposal

It becomes clear that pictures travel through bodily experience and circulate in networks in an incessant flow at varying speeds. In the end, they are continuously reproduced and transpired, no matter how unique their subjects may be (in both the literal and figurative senses). Mieke Bal, an eminent cultural theorist and art historian, addresses this premise in her theory of "image-thinking." Rather than seeing pictures as static representations devoid of real meaning and agency, "image-thinking" is a critical analysis and interpretation perspective that emphasises their inherent movement and volatility. The series of thoughts that follow her "image-thinking" reveals how the image is pre-positioned at the crossroads of our inner and outer worlds. Subsequently, we are soon forced to switch our passive and habitual ways of looking, where the picture itself now serves as the channel of thinking and where we no longer perceive ourselves as standing in front of a framed image but rather as passing through and beyond it—where one is seen in and through the other. Rather than just displaying a preset object, one could consider the form of exhibition making that focuses on the viewer's engagement, the thrill of inquiry, and the immediacy of the moment. This line of inquiry has not only served my exploration of framing devices for the image but also the curation of the gallery space when considering my unit three proposal; The body of the viewer is central to all these diverse practises, as "image-thinking" establishes a connection between them beyond medium barriers as tangential performance. In my exploration of framing space in the unit three exhibition, I hope to forge connections between artwork and audience by framing the space in parallel frames that embody both the paintings and participants. Mieke Bal argues that the "traditionally imposed mode of viewing governs the temporality of looking" (Bal, 2022, pg.6) in museums and galleries, highlighting the significance of time as a material component of the exhibition experience in "image-thinking." My work's critical investigation into picture's current transitive state rather than as instants of still life (the ways in which, by utilising the very framework of the work, I can make this perspectival shift tangible) generates a profound shift that is gaining crucial value with the advent of AI and NFTs. Thus, my work encourages us to contend with the drastic transformation of pictures into transmissions of data and visual information to face the drastically shifting hierarchies of pictures in contemporary culture.

Going to See a Man About a Dog, oil on canvas, painted frame, 21 x 29.7 cm (A4, unframed) 24 x 32.5 x 5.5 cm (framed)

By superimposing a displaced collage of the image down the middle of the image, I almost completely eradicate the man and the dog in "Going to See a Man About a Dog," so that only their silhouettes, now contained by the stripe that correlates with the proportions of the work's outer frame, remain visible to the viewer. By eliminating the total appearance of the man and dog and thus avoiding any real connection between the observer and the subjects being observed, the artwork presents only hints of the enigmatic entity of a body. Not only does the disruption of the work add to the tangible quality of images, but the fluidity of images is arrested rather than being disintegrated into disjointed units of data and visual stimuli just prior to their integration into the networks that govern them. Elad Lassry, an Israeli-American artist, thought of a number of ways to investigate and combat this scenario of the endless circulation of images, one of which is the emphasis on tangible support in his work. Specifically, Lassry's pictures and collages are often shown in frames painted to complement the dominant colour of the image at hand. Thus, he accomplishes a remarkable encapsulation of the actual image and its purported aesthetic tropes, which is resistant to the compression imagery is typically subjected to in our era of the networked image. Lassry's artistic approach involves the transformation of a potentially limitless image into a tangible, three-dimensional form. This form is not easily comprehensible in its entirety, except when displayed on the walls of a designated exhibition space. Consequently, viewers must devote significant time and attention to fully appreciate the intricate nuances of the artwork.

Elad Lassry, Beets, 2010, Chromogenic color print, frame, 29.2 x 36.8 cm

Elad Lassry, Untitled (Chaps), 2014, C-print, walnut frame, 4-ply silk, 36.8 x 29.2 x 3.8 cm

My paintings' titles barely go beyond denotations of what they purportedly portray, and yet their playfulness and use of English idioms are both alluring and empty; they seem to capitalise on the individuality of each object while also tending towards the universal. One example is my work "A Pipe Dream," in which the subject matter encompasses a pipe but the image has been cropped and isolated within a picture plane, eliminating all reference to its original setting. Since neither the source nor the intended application of the painting are directly evident, the artwork appears to be bereft of a contextual reference. My work is keenly attuned to the reality that transformations of a picture might appear in a variety of contexts and media. In essence, it tracks the unprecedented shift in the global economy of pictures, which inevitably profoundly affects painting and the field of contemporary art. Consequently, the work circumvents the tendency to revert to obsolete paradigms that support the notion of an immutable and autonomous artistic expression. Likewise, it avoids dependence on the notion of subversion, which in today's world merely perpetuates the mechanisms of the cultural sector that rely on novel aesthetic methods of compression.

Through this critical reflection, I hope to convey how the making and thinking processes I engaged in throughout Unit 2 are inextricably linked to the discourses and artists that serve as influences on my practise. Although there are several artists and authors who have had a significant effect on my work, I would be unable to give credit to them all within the confines of this targeted and brief 2000-word critical reflection. This is not to say, however, that they have not influenced key developments in my practise. On the contrary, these developments became enriched and deepened by the addition of in-depth analyses and reflections of their fields, which I hope I have highlighted well throughout my documentation and online platform.

References:

Bal, M 2022, Image-Thinking : Artmaking As Cultural Analysis, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [1 June 2023].

Extended Research

Xhibit - from / now / on

image credit: Peer Sessions

image credit: Peer Sessions

During the exhibition of Xhibit, I participated in a programme of events that stimulated discussion pertinent to a socially engaged practise. Artists were invited to present their work to the UAL SLT and ArtsSU staff alongside Sophie, who provided a summary of the exhibition's investigations and objectives. Before the exhibition's closing, artist Adam Cole and I joined Sophie Risner and Peer Sessions' Kate Pickering and Charlotte Warne Thomas for a safe space group critique. The crit provided an inclusive and secure environment for discussing in depth how the work is received and positioned within a gallery context. With nearly an hour allotted to discuss each work, I was pleasantly surprised by the attentive responses, generating thoughts that will lead me through postgraduate study and beyond. As accomplished artists and academics, this opportunity allowed for the generation of constructive feedback and sparked an open dialogue regarding contemporary issues in the world of arts and culture.

Weekend Arts, a London-based nonprofit that organises free monthly museum/gallery tours and activities for socially isolated individuals who prefer group settings, also extended an invitation to see the show. Many of the participants have been homeless or struggle with mental illness, but they are united by their enthusiasm for the arts and a desire to express themselves creatively. The goal of these outings is to make art available to people of all walks of life and backgrounds by removing obstacles to its inclusivity. It was an invaluable way for me to gain confidence in talking about my work while participating in dialogue with individuals from a variety of backgrounds, both of which are essential to making sure everyone feels welcome in creative spaces and has the opportunity to connect with art.

For the Post-grad Community, I published this piece I wrote on my experience of Xhibit on their website as part of their Post-grad Stories. You can check out the article here:

image credit: Peer Sessions

PhD Research

As documented in unit 2 assessment diagram, it is possible to extend research methods by, for example, conducting research in external collections or archives or in dialogue with researchers or professionals in other fields. This made me consider not only the dialogues I have had through my own practice and external engagement, but the dialogues that may arise from conducting PhD research when I feel ready to initiate contact with professionals that share similar research interests.

I have spent considerable time this academic year investigating the different funding sources and studentships available for doctoral candidates, as well as attending two research degree open days. After taking in a wide range of visual and theoretical discourse with my professors and peers this past year, I have begun to think about the research questions that have resulted from my practise and will drive my PhD dissertation. I have mostly used the evaluation and critique of existing information provided in the context page, documentation page, and critical reflection to guide the course of my research proposal and guarantee that my study will be novel and make a significant contribution to the area of knowledge as I advance my practise. I'm continuing working on my research project, which I want to complete with the help of the skills and information I've acquired this year. I have identified a small number of potential supervisors at a small number of universities that share my research interests; however, I have refrained from initiating dialogue with them until I have a firm grasp on my own research topics and have done more study into their own work and disciplines. After visiting the open houses, I am also aware that certain universities prefer applicants not to make preliminary contact with their prospective supervisors. Before the end of the course in November, which is when most PhD applications open, I'm hoping to have a solidified research question and proposal.

When it comes to PhD students in the arts and humanities, the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) is the primary funding body for the UK's government. An AHRC PhD studentship will provide financial support for tuition, living expenses, and professional development activities during the duration of the doctoral programme. Although I have looked into many different studentships and signed up for email notifications when more become available, I have not yet found any that align with my research interests (including UAL's 7 new CDPs to coincide with the new Doctoral School) and am therefore more likely to apply for funding through an AHRC DTP (Doctoral Training Partnership) than through a CDP (Collaborative Doctoral Partnership). In addition, I have explored other potential funding avenues, such as the Paul Mellon Centre PhD Scholarship, which is part of their 'New Narratives' initiative that aims to improve the variety of viewpoints among researchers in the area of British Art History. Some of the AHRC DTPs I looked into in and around London are listed here.

PhD funding - AHRC DTPs (Doctoral Training Partnerships)

London Arts & Humanities Partnership (LAHP)

University College London

King's College London

Queen Mary University of London

the Royal College of Art

University of London

Consortium for Humanities and the Arts South-East England (CHASE)

Goldsmith's College

Open-Oxford-Cambridge

University of Oxford

University of Cambridge

Open University

techne

Royal Holloway University of London

University of the Arts London

University of Brighton

Brunel University London

Loughborough University

Roehampton University

University of Surrey

University of Westminster

Kingston University